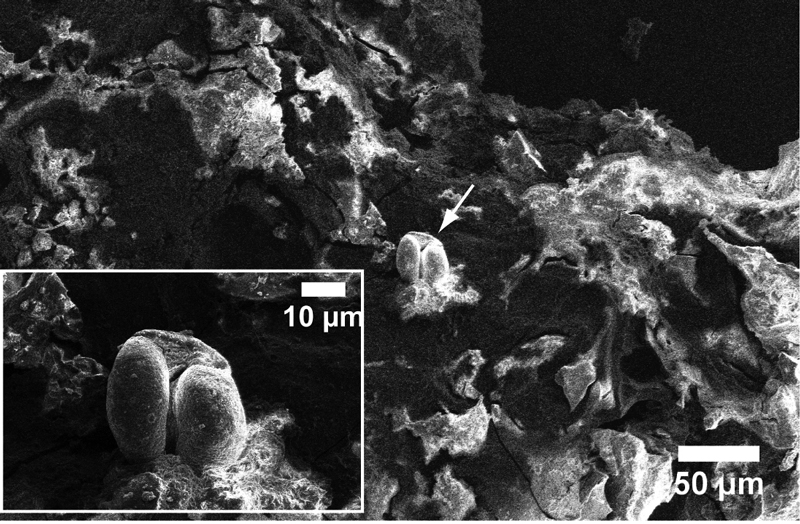

Scanning Electron Microscopy image, showing microscopic structure of the food crust from the rim of the ancient pot where carp caviar was found. Plant debris (with encrusted conifer pollen) indicate that the pot was probably tapped with leaves during cooking process. © Shevchenko et al. PLOS ONE. 28. Nov 2018 / MPI-CBG

Burnt food remains are very often found in pots from archaeological sites. Analyzing their protein content, helps us to understand many aspects of life in antiquity. The Mass Spectrometry Facility at the Max Planck Institute of Molecular Cell Biology and Genetics (MPI-CBG) in Dresden was approached by scientists from the State of the Brandenburg Authorities for Heritage Management and Archaeological State Museum (BLDAM) to analyze a clay bowl with burnt food remains, found at an archaeological site in the State of Brandenburg in Germany. Usually, the MPI-CBG Mass Spectrometry Facility provides a service for scientists. The team around Anna Shevchenko at the MPI-CBG developed a new proteomics analysis, identified over 300 proteins and was able to distinguish between ancient proteins and contemporary contaminants. In that way, they found fine carp roe in the charred remains of prehistorical food. They published their findings in the journal PLOS ONE.

Food crust are burnt food remains that are found on archaeological pottery. They are very difficult to analyse because ancient proteins are extensively degraded by cooking and natural aging as well as mixed with environmental contaminants, such as soil bacteria or plants. In 1979, archaeologists excavated fragments of 6000 years old pottery at the Friesack 4 Site, an archaeological site near Berlin in Germany, which is known for excellent preservation of numerous artefacts predominantly from Mesolithic era. The ancient ceramics were safely stored but at that time the technology to analyse them didn’t exist yet. So, the pottery waited until 2013, when they were re-discovered by scientists from the BLDAM. In the meantime, powerful protein analysis technologies had been developed. This is when the scientists from the Mass Spectrometry Facility of the MPI-CBG came into play. The colleagues from the BLDAM asked them if it was possible to analyse the food remains on a small clay bowl.

Finding out what was in the pot – origin and processing of ancient food – was the major question scientists asked themselves. Remains of ancient foods help us to understand many aspects of life in the European Inland in antiquity, like complex process of transformation from hunter-gatherer groups to sedentary society, diet and cooking practices, the role of natural resources in economy or the domestication of animals and plants. Anna Shevchenko explains the challenges, of analysing food remains: “We had to tackle the question of how food proteins survive in charred deposits on archaeological sherds and how we could distinguish original ancient proteins from modern contaminants, like human skin, saliva or plants once grown at the excavation field.” By quantitatively detecting aging-specific chemical modification, the scientists were not only able to exclude contemporary contaminants. They developed a completely new analytical method for proteins, that was able to identify major components of the food residues.

This newly developed proteomics analysis of food crusts identified up to 300 proteins in 6000 years old pottery, allowing for an evaluating the organismal origin and suggesting food processing technology. They found fish proteins that were matched to the common carp and specifically to caviar or roe. Proteomics analysis did not find evidences of fish fermentation, which suggests that the food was most likely thermally processed. Size and shape of the pottery, a charred crust, and the identification of a certain fish protein suggested that delicate carp roe might be cooked in a small volume of water or fish broth. Additional electron microscopy images suggest that the pot was probably covered with leaves. The analysis of other potsherds from the site also found pig collagen, which indicates that pork with bones, sinews or skin was cooked in this pottery. This correlates well with zooarchaeological artefacts from the site Friesack 4, which includes boar bones, and supports the notion that this site was used as a hunting station.

„The fact that the investigations with this new method could be carried out so successfully, using the example of over 6000-year old pottery from the site near Friesack, is probably a milestone in the approach to the habits of our hunter-gatherer ancestors,” explains Günter Wetzel, former archeologist at the BLDAM and co-author of the study. He continues: “At the same time, this method reminds the excavator to be even more careful with archeological finds from the time of their discovery, to make such investigations possible at all later on. The scientists from the MPI-CBG benefited from the fact that the head of excavations and former director of the Potsdam Museum of Prehistory and Early History Bernhard Gramsch, did not let the pottery to be washed after the discovery.”

Anna Shevchenko summarizes: “This study provides archaeologists and anthropologists with new analytical tools for studying dietary habits in prehistorical societies. In a broader perspective, it improves our ability to analyse proteomes from environmental samples originating from organisms with unknown genomes. The method opens new perspectives for proteomics studies of unconventional biological samples in life and medical sciences where proteins are trapped in mineral matrices such as tooth or bones, spicules, or shells.”

Picture Caption: Reconstruction of the 6000 years old pot from Friesack 4 archaeological site (upper panel) and a closeup view of the charred food crust at its bottom (lower panel) where scientists found remains of prehistorical caviar meal. © Shevchenko et al. PLOS ONE. 28. Nov 2018 / MPI-CBG / BL

Anna Shevchenko, Andrea Schuhmann, Henrik Thomas, Günter Wetzel: Fine Endmesolithic fish caviar meal discovered by proteomics in foodcrusts from archaeological site Friesack 4 (Brandenburg, Germany). PLOS ONE, 28 November 2018

Scanning Electron Microscopy image

Friesack Pottery and foodcrust